Patrick Britton

Published: May 01, 2016

The 31st of May 2016 is the centenary of the Battle of Jutland, the only major fleet action of the First World War. The battle is regarded as a tactical defeat in that Great Britain lost more ships, but a strategic victory in that the German fleet was largely confined to port for the rest of the war, and its disintegration into mutiny played a significant part in Germany's final collapse in 1918.1 One ship which narrowly missed taking part in the battle was the Royal Navy's aircraft carrier, HMS "Campania", the first ship ever to launch an aircraft while underway, and formerly RMS "Campania", a Cunard Line Royal Mail express steamer. This article discusses the history of "Campania" and whether her presence at the Battle of Jutland might have assisted the British Grand Fleet.

Ordered by the Cunard Line from the Fairfield Shipbuilding & Engineering Company Limited of Glasgow in August 1891, "Campania" and her sister ship "Lucania" achieved a number of 'firsts'.2 They were the first twin-screw ships built for the line, driven by two sets of five-cylinder triple-expansion engines. They were the first Cunard ships to abandon auxiliary sail power; the redundant masts were retained as flag poles. They were the first Atlantic liners to have refrigeration machinery, and among the first to offer first class passengers cabins with suites. The most expensive Cunarders yet built, costing £650,000 each, their lavish first class interiors were designed to make passengers 'feel they were at home with the aristocracy', or as one passenger remarked "Campania's general style is Italian somewhat sobered down by an air of British substantiality". At 12,950 tons and 620 ft long, "Campania" and "Lucania" were 'Atlantic greyhounds' built for speed, with their funnels raked backwards to enhance the impression of motion. "Campania's" maiden voyage from Liverpool to New York in April 1893 was the fastest to date and on her return leg she regained the 'Blue Riband' for Cunard, becoming the line’s first ship to cross the North Atlantic in less than 6 days at an average speed of above 21 knots.3 Together "Campania" and "Lucania" encapsulated the ideals, tastes and technological achievements of the Victorian age.

RMS "Campania" made 250 crossings between Liverpool and New York before she was retired from Cunard’s service in spring 1914. She returned to Cunard’s transatlantic service following the outbreak of war as her successor RMS "Aquitania" was requisitioned for trooping duties, but by the end of 1914 "Campania" had been sold for scrap.4 However, the Royal Naval Air Service ("R.N.A.S"),5 formed in July 1914, was in need of a large fast vessel for operations with the Grand Fleet and decided to convert "Campania" into the first Fleet Air Arm carrier. The conversion carried out at Cammell Laird's Birkenhead yard involved the removal of most of the passenger accommodation, and the creation of a vast hangar which extended up through the former first class dining saloon to a large hatchway on the boat deck. The hangar could house twelve Short 184 reconnaissance seaplanes stored with their wings folded back.6 The aircraft would be lowered into the water for take-off - no vessel existed with a flight deck at this time - and a seaplane tender (a high speed motor launch) carried on board would assist with their recovery. If the German fleet was spotted from the air, signals were to be sent using Very's Lights in code, such as red-green-green-red for 'enemy in sight'. Aircraft were also fitted with basic wireless sets.

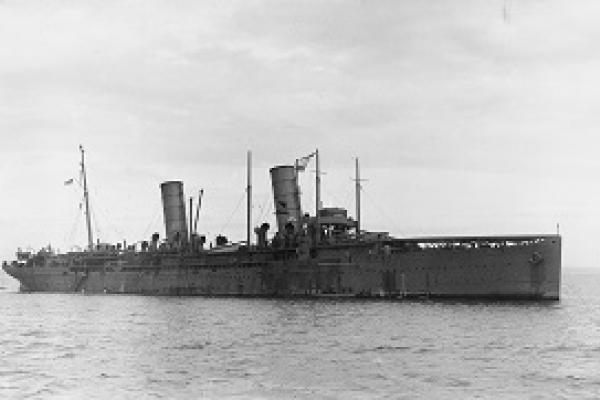

The conversion was completed by February 1915. Painted overall in wartime grey, the newly-commissioned HMS "Campania", under the command of Captain Oliver Swan,7 joined the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow for test flights. Launching the seaplanes proved difficult as the fragile machines were easily damaged during the lowering operation, as they smashed against the "Campania's" rolling sides. Once in the water, their floats tended to break off in heavy seas. On the suggestion of her Signals Officer, R. Leyland, Admiral Sir John Jellicoe ordered HMS "Campania" to return to Cammell Laird to have a large wooden flying deck constructed forward of her bridge. Attempts were then made to launch the seaplanes on wooden trolleys while the ship was underway. After much competition between the R.N.A.S. pilots, Lieutenant Breeze was selected to make the first take-off attempt. On 5th May 1915, with "Campania" steaming into a wind of about force 4, his Short 184 aircraft successfully took off, inaugurating a new era in sea warfare - the advent of the aircraft carrier. The seaplane landed on its floats and was recovered using the ship's tender and derricks.

After further test flights, it was soon realised that the flight deck was too short: instead of becoming airborne, the aircraft frequently plummeted off the end of the ship, earning the pilot and observer a swim in the cold North Sea. The regular sight of the white fuselage standing upright out of the water after another unsuccessful take-off led to "Campania's" crew nicknaming the Short 184 'The White Coffin'. Sailors looking on from the battleships of the Grand Fleet found it all hilarious. By May 1916 HMS "Campania's" flight deck had been extended and the angle of its rake increased. This necessitated removing her original forward funnel and replacing it with two smaller port and starboard funnels. "Campania" was also equipped with a Caquot kite balloon for short-range observation, and her aft mast was removed and aft deck cleared for this purpose. From a liner with handsome yacht-like lines, the modifications gave her a strange appearance, but she was now ready for war.

The German High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice-Admiral Reinhard Scheer, had been blockaded in the North Sea since the start of the war by the British Grand Fleet, based at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands under Admiral Jellicoe. The German naval command wished to avoid risking the High Seas Fleet in an encounter with the superior strength of the entire Grand Fleet. As long as the High Seas Fleet continued to exist, the Grand Fleet was tied down maintaining the blockade and its escorts could not join the fight against Germany's submarine fleet attacking the Allied merchant ships. Nevertheless, Vice-Admiral Scheer hoped to provoke a battle between the full strength of the High Seas Fleet and a detached portion of the Grand Fleet, specifically, the British Battle Cruiser fleet - the Grand Fleet's reconnaissance and mobile striking arm based at Rosyth under Vice-Admiral Sir David Beatty. If British naval strength could be eroded, the High Seas Fleet might stand a chance of taking on a diminished Grand Fleet. However, there was a major flaw in Scheer's plan: British cryptanalysts had deciphered German naval codes, and although the intelligence was often sketchy, Jellicoe had prior warning of many of his deployments. Thus when the High Seas Fleet departed its North Sea bases on 31st May 1916, Beatty's Battle Cruiser Fleet was already sailing to intercept it, as Scheer hoped it would, but so was the entire Grand Fleet.

Unfortunately when the Grand Fleet left its base on 30th May 1916, HMS "Campania" remained behind. Why this happened is not entirely clear. She may have been anchored in a remote part of Scapa Flow, or she may have not entirely received the signal to sail, or her aircraft may have been ashore. Once the mistake was identified, four hours passed before she was able to depart with her two escorting destroyers. Steaming at her full speed of 19.5 knots she was unable to match the Grand Fleet's speed of 22 knots. As the gap widened, Jellicoe ordered her back to Scapa Flow, fearing she would be torpedoed. Thus Jellicoe had to fight the Battle of Jutland without being able to use his air reconnaissance to locate the enemy.8 Scheer had a fleet of five zeppelins for air reconnaissance, but bad weather on 31st May delayed their launch and they were unable to arrive at their patrol areas in time. However, it is unlikely that the airships would have been able to see much owing to hazy conditions and a 1,000 ft cloud base.

The Battle of Jutland was fought at a range of between 10,000 and 18,000 yards.9 Jellicoe relied on his squadron commanders to keep him informed of the position of the High Seas Fleet, but in the heat of the action they frequently failed to do this, or their reports lacked essential information. Communications relied primarily on flags and signal lights, which were often too far away to make out, and on wireless, but wireless messages relayed between ships often suffered mutilation or were garbled. As Jellicoe wrote later to the First Lord of the Admiralty: "The whole situation was so difficult to grasp, as I had no real idea of what was going on and we could hardly see anything except the flashes of guns, shells falling, ships blowing up, and an occasional glimpse of an Enemy vessel." 10 Inadequate communications meant Jellicoe had to deploy the Grand Fleet into line to take up battle formation based on guesswork, and delayed engaging the High Seas Fleet in conditions of fast diminishing visibility. It is unsurprising that Scheer's fleet was able to escape during the night. HMS "Campania's" reconnaissance aircraft may have enabled Jellicoe to deploy more quickly and to begin the battle earlier than late afternoon.

The British ships had other major problems at Jutland. Most serious was the dangerous way cordite propellant was stored in the gunhouses, and magazine doors left open, in order to maximise rate of fire, and this resulted in three battle cruisers, HMS "Invincible", HMS "Indefatigable" and HMS "Queen Mary", blowing up. The mismatch between the slow development of communications technology in contrast to the rapid development of the speed of warships, the power and range of their guns, and the fire control equipment available, is one of the most notable aspects of naval warfare of the era. The British may have expected a 'second Battle of Trafalgar', but Admiral Lord Nelson would have had a much better idea of what was happening from HMS "Victory's" quarterdeck at Trafalgar than Admiral Jellicoe did from the bridge of his flagship HMS "Iron Duke" at Jutland. Whether the aircraft of HMS "Campania" would have helped is a matter of conjecture.

On 5th November 1918, six days before the end of the war, HMS "Campania" collided with the battleship HMS "Royal Oak" and the battle cruiser HMS "Glorious" in the Firth of Forth, after dragging her anchor in high winds. The resultant hull breach caused her engine room to flood and with the ship settling by the stern, her crew was safely evacuated. HMS "Campania" sank five hours after the initial damage when a boiler exploded, sending her to the seabed. With the tops of her masts visible at low tide, the wreck was deemed a serious menace to navigation, and was later blown up.

1 Out of 144 British and 125 German warships involved in the Battle of Jutland, British casualties amounted to 6,600 men and 14 ships, while German casualties numbered 3,076 men and 11 vessels.

2 Most Cunard ships were given Latin names for land masses ending in 'ia'. Campania was the Roman province whose present day capital is Naples. Lucania is the region in southern Italy between Campania and Calabria.

3 "Campania" captured the 'Blue Riband', an accolade given to the fastest passenger liner crossing the North Atlantic based on average speed, from the Inman Line's "City of New York" of 1888. "Lucania" was slightly faster and held the speed record for Cunard from 1894 until 1897, when Norddeutscher Lloyd's 14,349 ton "Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse", the world's then largest ship, captured the record for Germany.

4 "Lucania" was de-commissioned in 1909 and on 14th August that year she caught fire and sank while laid up in Liverpool docks. She was later salvaged and scrapped.

5 On 1st April 1918 the R.N.A.S. was merged with the British Army's Royal Flying Corps to form the Royal Air Force.

6 The Short 184 biplane had a single 225 hp Sunbeam engine to power it along at 80 mph, it carried two & three-quarter hours' fuel and could climb to a maximum height of 9,000 ft in a minimum time of three-quarters of an hour. It was built by Messrs Short Brothers of Rochester and Bedford.

7 Her First Lieutenant was Charles Herbert Lightoller, a Royal Navy Reservist and formerly Second Officer of RMS "Titanic", the most senior surviving officer of the tragedy.

8 Beatty's fleet included a seaplane carrier HMS "Engadine", a converted channel ferry, but she lacked a flight deck and only one of her Short 184s managed to take off from the sea owing to rough weather. It made three sighting reports but "Engadine" was unable to communicate these to Beatty.

9 9 - 16 km

10 A Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow, Vol III (Oxford, 1961), p.110.